I know, the title sounds intriguing boring and in effect it is.

When I started my PhD I did not even know what spatial statistics exactly was. It was my inspiring colleague, Dr. Giacomo Benini, who introduced me to that. My PhD is in Demography, more precisely on migration studies. So why should not I apply some spatial statistics to human migration movements? Most of the time I think I have come up with a brilliant idea someone else has already had it. I am sure it is a common feeling. You honestly did not know that another person has thought about it before and you are so annoyed by discovering that you are just the Nth person with the same intuition. So with an already disillusioned spirit I started my literature review in search of what has been already done on terms of spatial statistics and human migration data. Believe it or not, for once, I found very little. When you find little already done about your idea you start thinking that what you have in mind is impossible, and this was my second thought. However, you can guess how the story ends and if I am writing a post, it means that I was somehow capable to create something out of that first idea.

What is Spatial Statistics about?

The adjective spatial reminds of geography that is where spatial statistics has first found most of its applications. It originates form Tobler’s First Law of Geography: “Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”. The concept of Tobler’s Law is that closer things have more in common, maybe because they influence each other through spillover effect. Nevertheless, the meaning of closer does not have to rely exclusively on geographical distance. It can be anything that two things have in common, such as states with the same spoken languages. Therefore, spatial statistics is all about cross-sectional dependence, that is the influence one cross-sectional unit has on another one. Said differently, it is about trying to take into account spillovers which, if neglects, might bias your estimates.

When do we apply Spatial Statistics?

Most of the time it is applied to macro dataset, which have few units observed over a relatively long time period. A common example is when cross-sectional units are counties or industries. Micro datasets, instead, usually have a lot of IDs observed for a relatively short period of time. It is intuitive to think that two countries which share the same languages, are more likely to influence each other rather than two people who speak the same language.

The Migration Context

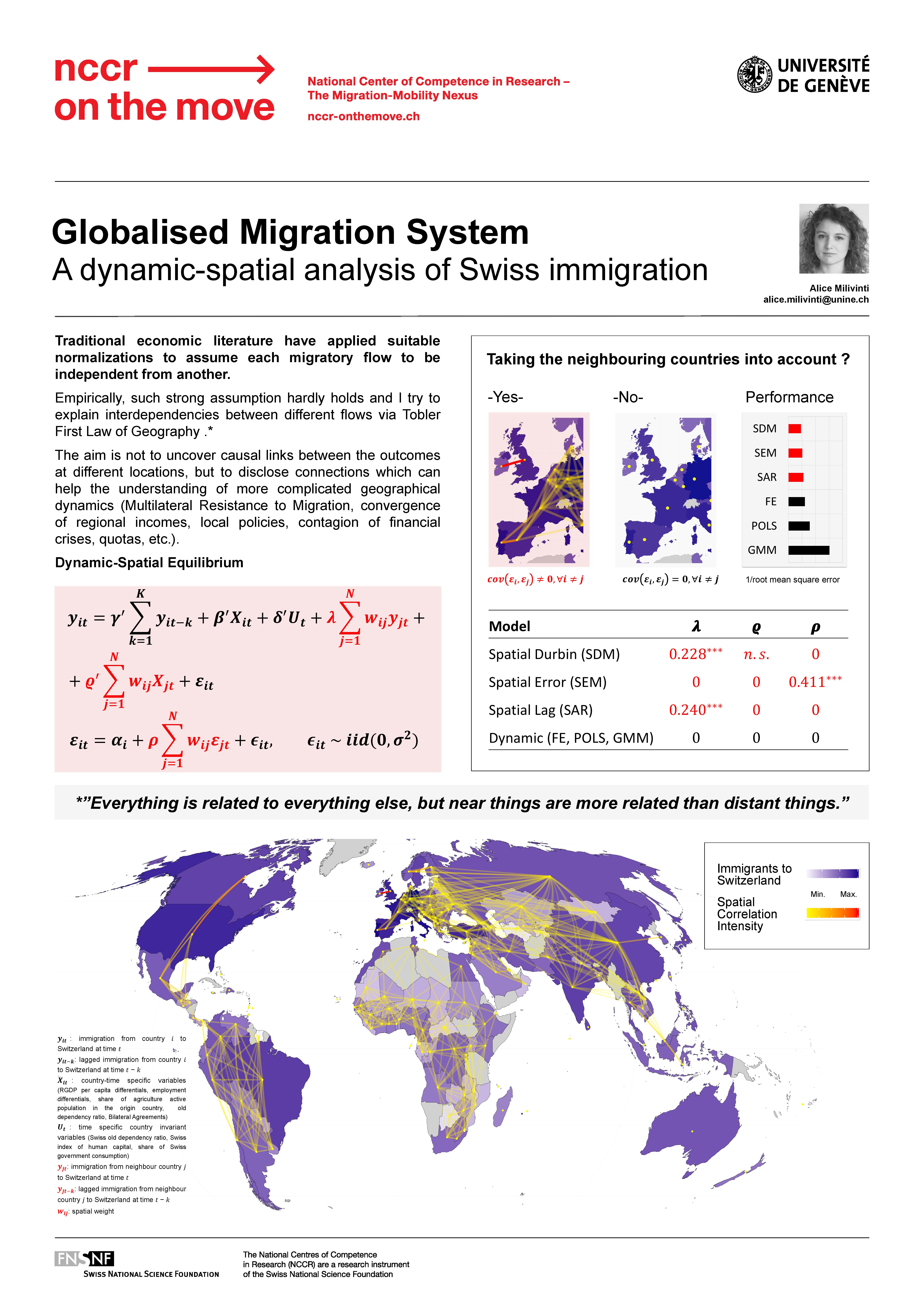

How do I apply Spatial Statistics to the migration context? My interest is to accurately predict the number of inflows to Switzerland from different origin countries. Specifically, I want to compare spatial and non spatial models to check if the negligence of a correct treatment of the spatial dependence would have importantly bias the estimates.

My Contribution

Have the migration literature completely forgotten about the interdependence between migratory flows? Not really. In order to avoid the presence of interdependence between migration flows, the economic migration literature estimated the migration ratios, rather than the number of migrants. Migration ratio is the number of people moving from one origin to one destination divided by the total population of the origin (movers / stayers). Theoretically, this would have guarantee the independence under some specific assumptions. However, in these circumstances, what is estimated is not the number of migrants, but the percentage of migrants in the entire population. I was unsatisfied with this option since I wanted to predict the number of migrants. With migration shares everything gets more complicated since you need to predict both the total population as well as the movers.

I thought that, instead of insuring the independence among migration ratios, I would have rather tried to model the interdependence of migration flows through spatial models. For those who like equations (like me) my final poetic expression is:

\[y_{it} = \gamma y_{it-1} + \beta' X_{it-2} + \lambda \sum\limits_{j \neq i} w_{ij} y_{jt} + \pi\sum\limits_{j \neq i} w_{ij} y_{jt-1} + \varrho' \sum\limits_{j \neq i} w_{ij} X_{jt-2} + \alpha_i + \epsilon_{it}, \\ \quad \epsilon_{it} \sim iid(0, \sigma^2)\]

where, the dependent variable \(y_{it}\) is the value of immigration from the origin country \(i\) to the Switzerland. The first element on the right hand side of the estimation equation, \(y_{it-1}\) is the lagged value of immigration from country \(i\) to Switzerland at time \(t-1\) since migration is a path-dependent process. \(X_{it-2}\) is a vector of country and time specific variables lagged to \(t-2\) to deal with potential endogeneity. \(y_{jt}\) is the number of migrants moving from a neighbouring origin country \(j\) to Switzerland at time \(t\) and \(y_{jt-1}\) is the corresponding autoregressive term. Finally, \(X_{jt-2}\) is the vector of exogenous variables of country \(j\). The error term is composed by \(\alpha_i\), the unit-specific effect, \(\alpha_{t}\), the time-specific effect and \(\epsilon_{it}\), the random noise.

Results

Results support the initial intuition since not only have spatial coefficients been demonstrated to be significant, but also spatial model predictions have outperformed the established dynamic one in terms of root mean squared forecast errors (RMSFE) and mean absolute prediction error (MAPE). In particular, the importance of the lagged spatial autoregressive endogenous variable (\(y_{jt−1}\) ) emerged over the one of the lagged dependent variable (\(y_{it−1}\)). Although the evolution of migration dynamics remains highly volatile, the analysis has tried to show the importance not only of path-dependency, but also of cross-countries spillovers.

Poster presentation

A brief visualization of the research (not the most updated version of the article).